A Century of Political Clashes with the Legal Establishment: From FDR’s War on Big Law to Trump’s Executive Orders

Many Washington, DC establishment lawyers appear to lack the thick skin or intellectual rigor required for the practice of law

In the wake of recent reports that the Trump administration is “pressuring” law firms to shift their pro bono work toward conservative causes, critics have claimed that these tactics are unprecedented. That claim is historically shallow and shortsighted.

American presidents have always battled against the legal establishment when their agendas conflicted with the entrenched interests represented by so-called “powerful” law firms. This phenomenon is not new. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s confrontations with Big Law during the New Deal provide a crucial historical parallel to Trump’s recent actions.

The difference?

Beyond the obvious—that many lawyers in Washington, DC, appear to lack the thick skin or intellectual rigor required for the practice of law—Trump’s efforts are met with louder cries of outrage from a legal community that, at least in my experience, is a bastion of progressivism and anti-conservative causes.

Is this another chapter in a long-running conflict between ambitious executives and conservative lawyers, or something fundamentally new?

Roosevelt’s New Deal aimed to reshape the American economy and expand the federal government’s role to address the devastating impact of the Great Depression. This sweeping regulatory effort inevitably clashed with the interests of corporations and the influential law firms that represented them.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), a centerpiece of the New Deal, aimed to regulate industry through codes promoting “fair” competition and labor standards. The Schechter Poultry Corporation challenged the law, arguing it exceeded federal authority under the Commerce Clause.

Prominent lawyers represented Schechter Poultry in a case culminating in a unanimous Supreme Court decision, ALA Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935), striking down the NIRA as unconstitutional. Roosevelt reacted angrily to what he saw as a judicial conspiracy led by conservative lawyers protecting corporate interests over the nation’s welfare.

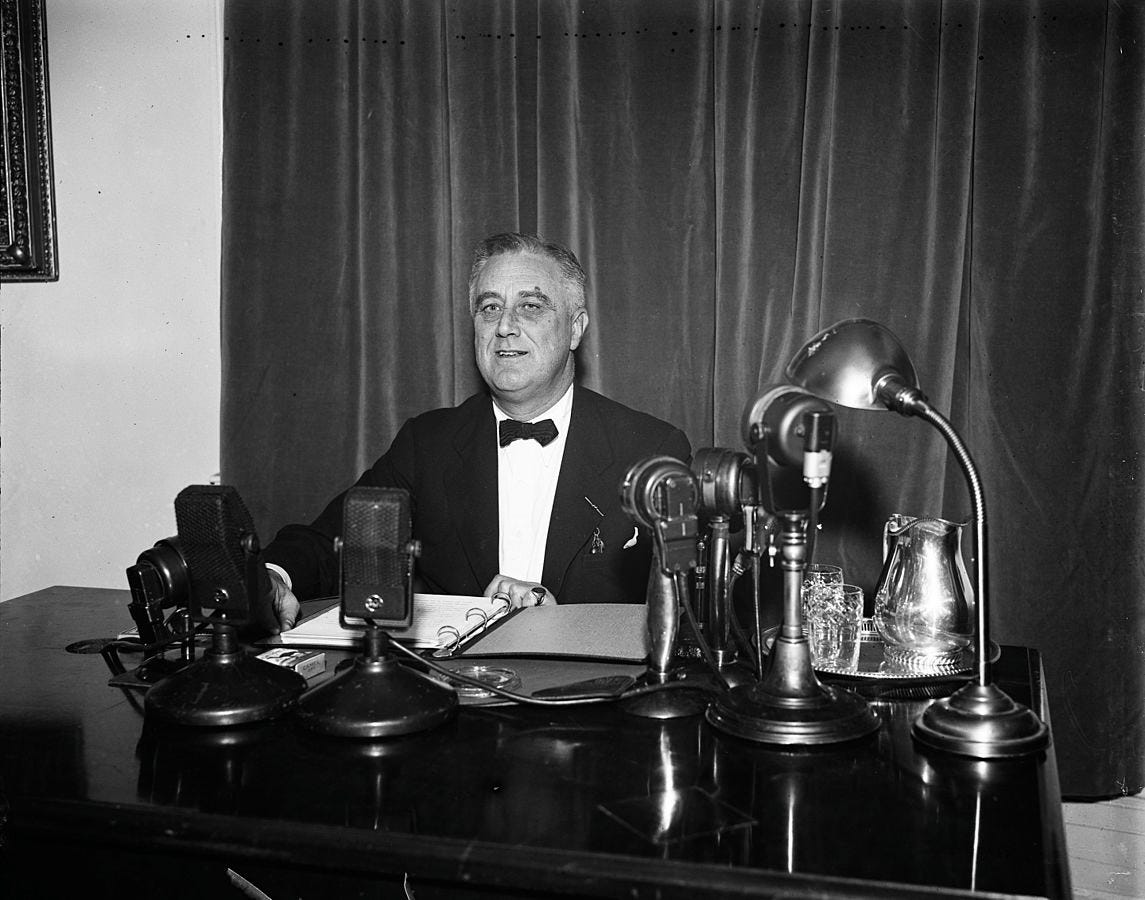

Consider FDR’s tone in his infamous Fireside Chat on March 9, 1937 (audio), during the Court Packing controversy:

“...four Justices ruled that the right under a private contract to exact a pound of flesh was more sacred than the main objectives of the Constitution to establish an enduring Nation.”

“We then began a program of remedying those abuses and inequalities - to give balance and stability to our economic system - to make it bomb-proof against the causes of 1929.”

“The Courts, however, have cast doubts on the ability of the elected Congress to protect us against catastrophe by meeting squarely our modern social and economic conditions.”

“When the Congress has sought to stabilize national agriculture, to improve the conditions of labor, to safeguard business against unfair competition, to protect our national resources, and in many other ways, to serve our clearly national needs, the majority of the Court has been assuming the power to pass on the wisdom of these acts of the Congress - and to approve or disapprove the public policy written into these laws.”

“…some members of the Court that something in the Constitution has compelled them regretfully to thwart the will of the people.”

“We want a Supreme Court which will do justice under the Constitution and not over it.”

“The Court in addition to the proper use of its judicial functions has improperly set itself up as a third house of the Congress - a super-legislature, as one of the justices has called it - reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there, and which were never intended to be there.”

“We have, therefore, reached the point as a nation where we must take action to save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself.”

Keep in mind the times. The Internet and X of the day were the radio. We had no Fox News or 24-hour cable channels. People read newspapers, and culturally, Americans were far less blunt in public discourse than they are today. Roosevelt’s words, delivered directly to millions of Americans over the radio, were fiery and provocative, especially from a sitting President. His tone and directness were remarkable, given the era’s more formal and restrained political communication style.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Poblete Dispatches to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.